Probabilistic methods in Ramsey theory

How far do we need to zoom in on a complex network to find an “ordered” subnetwork? To name a particular case: at a party with $n$ guests, can we find a group of $k$ among which either all pairs are friends or all pairs are strangers? Ramsey theory gives us one view on this question.

Theorem (Ramsey, 1930). For any $k \in \mathbb N$, there exists $n \in \mathbb N$ such that for any way we color the edges of the complete graph $K_n$ red or blue, it must have a subgraph of size $k$ with all edges the same color (a.k.a. monochromatic $k$-clique). Let $R(k)$, or “the $k$th Ramsey number,” be the least such $n$.

Proof. See Wikipedia.

Let’s compute some Ramsey numbers.

- $R(1)$. A subgraph of size 1 has no edges, so trivially any graph’s size-1 subgraphs are monochrome. The singleton $K_1$ is the smallest, so $R(1) = 1$.

- $R(2)$. A 2-clique has 1 edge, and hence is also trivially monochrome. $K_2$ is the smallest graph with a 2-clique, so $R(2) = 2$.

-

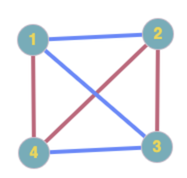

$R(3)$. Could it be 3? No — color two edges of the triangle red and the other blue. 4? No — fiddling around with $K_4$, it’s easy to come up with a coloring with no monochrome triangles:

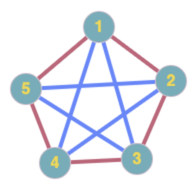

5? Again, no. Here’s a (in fact the) counterexample:

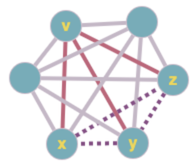

6?! Let’s try to argue that $K_6$ must have a monochrome 3-clique. Take vertex $v$, which has degree 5. At least 3 of its incident edges are red (if not, s/red/blue WOLOG); call them $vx, vy, vz$. If any of the edges $xy, yz, zx$ is red, then one of the triangles $\Delta vxy, \Delta vyz, \Delta vzx$ is all red; otherwise $\Delta xyz$ is all blue.

Yes, $R(6) = 6$!

Pencil-and-paper exploration hits the wall around this point. It turns out that $R(4) = 18$, but, amazingly enough, we don’t even know $R(5)$. (It’s somewhere between 43 and 48.) To make progress at greater $k$, we’re left to search for bounds. For upper bounds, we can establish $R(k) \leq u$ either by verifying that all possible 2-colorings of $K_u$ (there are $2^{n(n-1)/2}$ of them!!) have a monochromatic $k$-clique or, more realistically, come up with some stuffy mathematical argument. For lower bounds, we can “simply” find a coloring of $K_\ell$ with no monochromatic $k$-clique to show $R(k) \geq \ell$, as we did for $k=3$ above.

The key insight of Erdős’ probabilistic method is that we can “hack” the lower-bound-finding process with a bit of nondeterminism: instead of constructing explicit colorings of $K_\ell$, we can specify some probabilistic procedure for coloring $K_\ell$ and then show that

\[P(\text{colored $K_\ell$ has a monochromatic $k$-clique}) < 1.\]The interesting bit is specifying a procedure that admits a nice analytical bound on this probability. Wonderfully, the simplest possible idea bears fruit:

Theorem (Erdős, 1947). $R(k) \geq 2^{k/2}$.

Proof. Let $\ell = 2^{k/2}$. Color each edge of $K_\ell$ red or blue independently at random with probability $1/2$. Consider any subgraph $C \subseteq K_\ell$ of size $k$. It has ${k \choose 2} = k(k-1)/2$ edges, and thus is all red with probability $1/2^{k(k-1)/2}$, or monochrome with probability $2^{1 - k(k-1)/2}$. There are ${\ell \choose k}$ choices of $C$, so

\[\begin{align*} p &:= P(\text{colored $K_\ell$ has a monochromatic $k$-clique}) \\ &= P(\text{some $C$ is monochrome}) \\ &\leq \sum_{\text{subgraphs $C$}} P(\text{$C$ is monochrome}) \\ &= {\ell \choose k} \cdot 2^{1 - k(k - 1)/2} \\ &\leq \frac{\ell^k}{k!} \cdot 2^{1-k(k-1)/2} \\ &= \frac{2^{k^2/2 + 1 - k^2/2 + k/2}}{k!} \\ &= \frac{2^{1 + k/2}}{k!} \\ &< 1, \end{align*}\]where the first inequality is due to the union bound, the second is a common upper bound for the binomial coefficient, and the third is intuitive given the hyperexponential growth of the factorial function — sub in Stirling’s approximation if you like.

In sum, just by telling monkeys to throw darts, we’ve proven (nonconstructively, with a bit of a smirk) the existence of “disordered” graphs of a certain size. How good is this bound? Pretty damn good, actually — it stood for 27 years, after which it was improved by only a factor of 2 by Joel Spencer.

This general program turns out to be useful for related analyses of ordered subnetworks. Probabilistic methods yield bounds on the sizes of graphs of a given girth, with a given number of Hamiltonian paths, with a given chromatic number, etc. I won’t get into that here.

When I came across this stuff in undergrad it struck me as an unexpected intrusion by the messy monkey world into the palace of math, kind of a for-lack-of-a-better-word “punk” union of ideas. I hope you find it as fascinating as I did.