Project Euler #111: Prime-Fu in Rust

Project Euler is very special to me. I found it in high school before I had any exposure to programming or CS. Guided by its many fascinating problems and solution forums, I taught myself to code — first in Java, then in Python, then in Haskell, which I discovered through some freaky one-liners in the solutions vault. I also discovered high-octane CS concepts that I didn’t understand at the time but whose mystery encouraged me to dive into the field in college.

Problem 111 asks us to compute $\Sigma(10)$, where

\[\begin{align} \Sigma(n) &= \sum_{d=0}^9 S(n, d), \\ S(n, d) &= \sum_\text{$n$-digit primes $p$} p \mathbb I[\texttt{n_occs}(p, d) = M(n, d)], \\ M(n, d) &= \max_\text{$n$-digit primes $p$} \texttt{n_occs}(p, d), \\ \texttt{n_occs}(p, d) &= \text{number of occurrences of digit $d$ in $p$}. \end{align}\]That is, for each decimal digit $d$, we must find the maximal number of times it can occur in a 10-digit prime and sum up all the primes with this maximal number of $d$s. For example, $d=1$ can occur at most 3 times in a 4-digit prime,

\[S(4, 1) = 1117 + 1151 + 1171 + 1181 + 1511 + 1811 + 2111 + 4111 + 8111 = 22275,\]and $\Sigma(4) = 273700$.

Brute force + Python

The dumbest possible code in the least performant possible language rarely does an Euler problem solve. That’s not gonna stop this rat from pulling the sugar lever:

from sympy import sieve

# Number of occurrences of digit `d` in integer `n`

def n_occs(n, d):

return sum(c == str(d) for c in str(n))

def S(n, d):

max_occs = 0

s = 0

# Check all `n`-digit primes, keeping sum for running max `n_occs`

for p in sieve.primerange(10 ** (n - 1), 10**n):

occs = n_occs(p, d)

if occs > max_occs:

max_occs = occs

s = p

elif occs == max_occs:

s += p

return s

n = 10

print(sum(S(n, d) for d in range(10)))

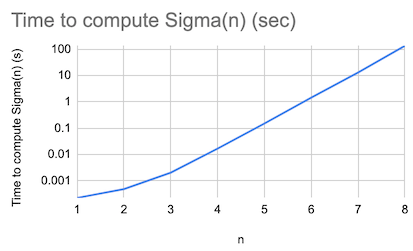

I’m not willing to wait around for this code to complete. The trouble with brute force, of course, is that the prime-counting function $\pi(x)$ grows as $x/\log x$, so our code’s runtime should be just about exponential in n. Indeed it is:

Extrapolating out the exponential fit suggests $\Sigma(10)$ will take about 3 hours to compute. Hey, if we can get a ~50x speedup from a bare-metal language, this will take under 4 minutes. How about Rust?

Brute force + Rust

After writing out the Python I saw a simple optimization: rather than iterating through all n-digit primes for each d to find the maximum number of digit occurrences, we can just scan once and maintain a single 10-vector of running maximum digit_counts. I don’t think this insight is enough to drop the “brute force” designation, though.

use primal::{self, Sieve};

fn digit_counts(mut p: usize) -> [usize; 10] {

let mut counts = [0; 10];

while p > 0 {

let d = p % 10;

counts[d] += 1;

p /= 10;

}

return counts;

}

fn sigma(sieve: &Sieve, n: u32) -> usize {

let mut max_digit_counts = [0; 10];

let mut ss = [0; 10];

let min_p = usize::pow(10, n - 1);

for p in sieve.primes_from(min_p).take_while(|x| *x < 10 * min_p) {

let counts = digit_counts(p);

for d in 0..10 {

if counts[d] > max_digit_counts[d] {

// We have a new max repeat digit count; reset count and sum

max_digit_counts[d] = counts[d];

ss[d] = p;

} else if counts[d] == max_digit_counts[d] {

ss[d] += p;

}

}

}

return ss.iter().sum();

}

fn main() {

let n = 10;

let sieve = Sieve::new(usize::pow(10, n));

println!("{}", sigma(&sieve, n));

}

Nothing interesting here, just brushing up on Rust semantics. This runs in about 2 and a half minutes on my machine — we got the speedup we wanted! However, 1-5 minutes is the uncanny valley of Euler solution runtimes: you’re definitely missing something big if it’s taking this long. Okay, let’s try to find that big thing, and stick with Rust for fun.

Earnest attempt + Rust

What’s killing us is obviously iterating over $\pi(10^{10}) - \pi(10^9) \approx 10^{10} / \log 10^{10} \approx 400\text{M}$ primes. That’s a lot of primes — so many, in fact, that I wager we are highly likely to find an n-digit prime with n-1 or n-2 occurrences of any digit. Furthermore, in general there aren’t that many n-digit numbers mostly containing a single digit d. Rather than taking primes and checking if they have a lot of ds, can we generate numbers with a lot of ds and check if they’re prime?

use itertools::Itertools;

use primal::is_prime;

// Get `n`-digit number with `free_digits` at given indices and `d`s elsewhere

// Ex: build_number(4, 1, [5, 6], [0, 2]) => 5161

fn build_number(

n: usize,

d: usize,

free_digits: &Vec<usize>,

free_digit_indices: &Vec<usize>,

) -> Option<usize> {

let mut digits = vec![d; n];

for i in 0..free_digits.len() {

digits[free_digit_indices[i]] = free_digits[i];

}

if digits[0] == 0 {

// Not an n-digit number

None

} else {

let number = digits.iter().fold(0, |n, d| n * 10 + d);

Some(number)

}

}

// Get all `n`-digit integers with `k` occurrences of digit `d`.

fn n_digit_numbers_with_k_ds(n: usize, k: usize, d: usize) -> Vec<usize> {

let n_free_digits = n - k;

let non_d_digits = (0..10).filter(|x| *x != d);

// Get all `n_free_digits`-tuples of non-`d` digits

let free_digits_choices = vec![non_d_digits; n_free_digits]

.into_iter()

.multi_cartesian_product();

// Order matters in free digits (e.g. we have both [1, 2] and [2, 1]), so order-independent

// combinations of indices suffice to construct all integers

let free_digit_indices_choices = (0..n).combinations(n_free_digits);

let mut numbers = Vec::new();

for free_digits in free_digits_choices {

for free_digit_indices in free_digit_indices_choices.clone() {

match build_number(n, d, &free_digits, &free_digit_indices) {

Some(n) => numbers.push(n),

None => (),

}

}

}

numbers

}

fn s(n: usize, d: usize) -> usize {

// Consider first `n`-digit primes with `n` `d`s, then `n-1` `d`s, etc. We can stop as soon as

// we find a nonempty set.

for k in (0..n + 1).rev() {

let mut n_digit_primes_with_k_ds = n_digit_numbers_with_k_ds(n, k, d)

.into_iter()

.filter(|p| is_prime(*p as u64))

.peekable();

if n_digit_primes_with_k_ds.peek().is_some() {

return n_digit_primes_with_k_ds.sum::<usize>();

}

}

panic!();

}

fn main() {

let n = 10;

println!("{}", (0..10).map(|d| s(n, d)).sum::<usize>());

}

This runs in a fraction of a second.

This last implementation ended up being a fairer fight against the compiler than I care to admit, with iterators and the borrow checker knocking me back at every turn. It’s very hard to imagine a case for Rust being in your top 3 tools for Project Euler. But it’s fun!